A detailed analysis suggests that COVID deaths and other pandemic-related mortality may have been significantly undercounted in the rural South and West

The U.S. has suffered an immense loss of life during the pandemic, with the official death count at well more than half a million to date. But the real number is likely even greater. A new analysis has found major variations in the rates of deaths assigned to COVID among individual counties—likely a result of socioeconomic and political factors.

Officially reported COVID deaths may not reflect the reality on the ground because of testing shortages, overwhelmed health care systems and differences in how deaths are registered. So researchers have been examining the number of last year’s “excess deaths” (those above the expected level, based on previous years) to seek a fuller picture of the pandemic’s impact. Earlier excess death studies, conducted at the national and state level, have suggested COVID deaths have been undercounted. But there has been less research on these trends at a more granular level.

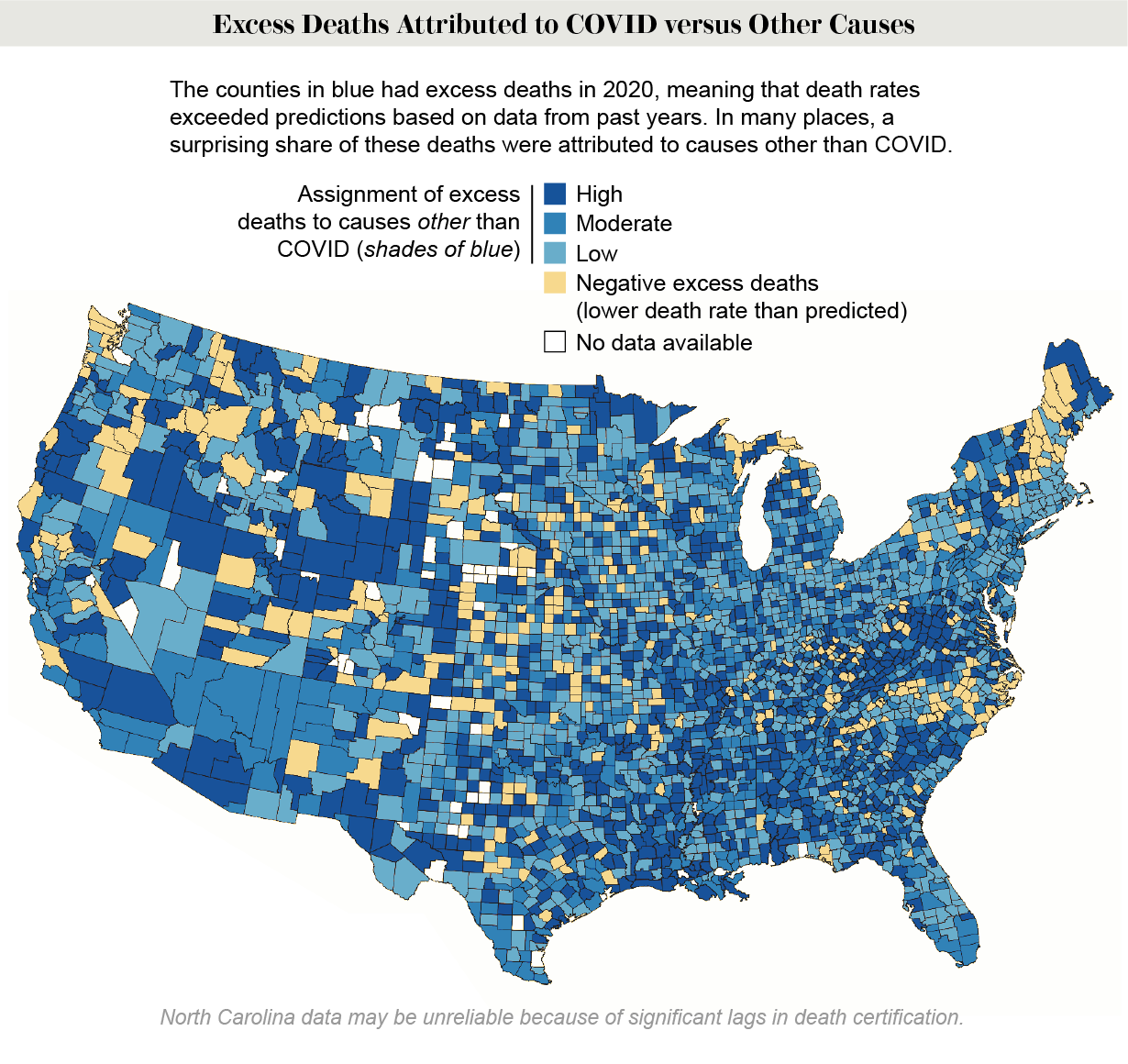

Andrew Stokes, an assistant professor in the global health department at Boston University, and his colleagues calculated excess deaths for each of more than 3,100 U.S. counties. To do so, they compared provisional 2020 mortality data from the National Center for Health Statistics with predicted death rates based on previous years. The researchers then compared the proportion of excess deaths attributed to COVID on death certificates with those assigned to other causes. Their data showed that 18 percent of excess deaths across the U.S. last year were not assigned to COVID. And rural counties in the South and West—particularly in the East South Central region—had some of the highest rates of excess deaths assigned to non-COVID causes.

The findings add to the evidence that a significant number of COVID deaths may have been undercounted. They could also reflect an increase in other types of deaths caused by the pandemic’s social and economic effects, often among disadvantaged populations.

“One consequence of underreporting of COVID-19 deaths in a community is that it may create the appearance that the pandemic did not affect that community and that the nonpharmaceutical interventions, vaccination and other preventive measures are not necessary,” Stokes warns. “People act on information. And if they’re not seeing COVID-19 mortality in their communities, they’re less likely to act.”

The findings were reported this spring in a preprint study that has not yet been peer-reviewed.

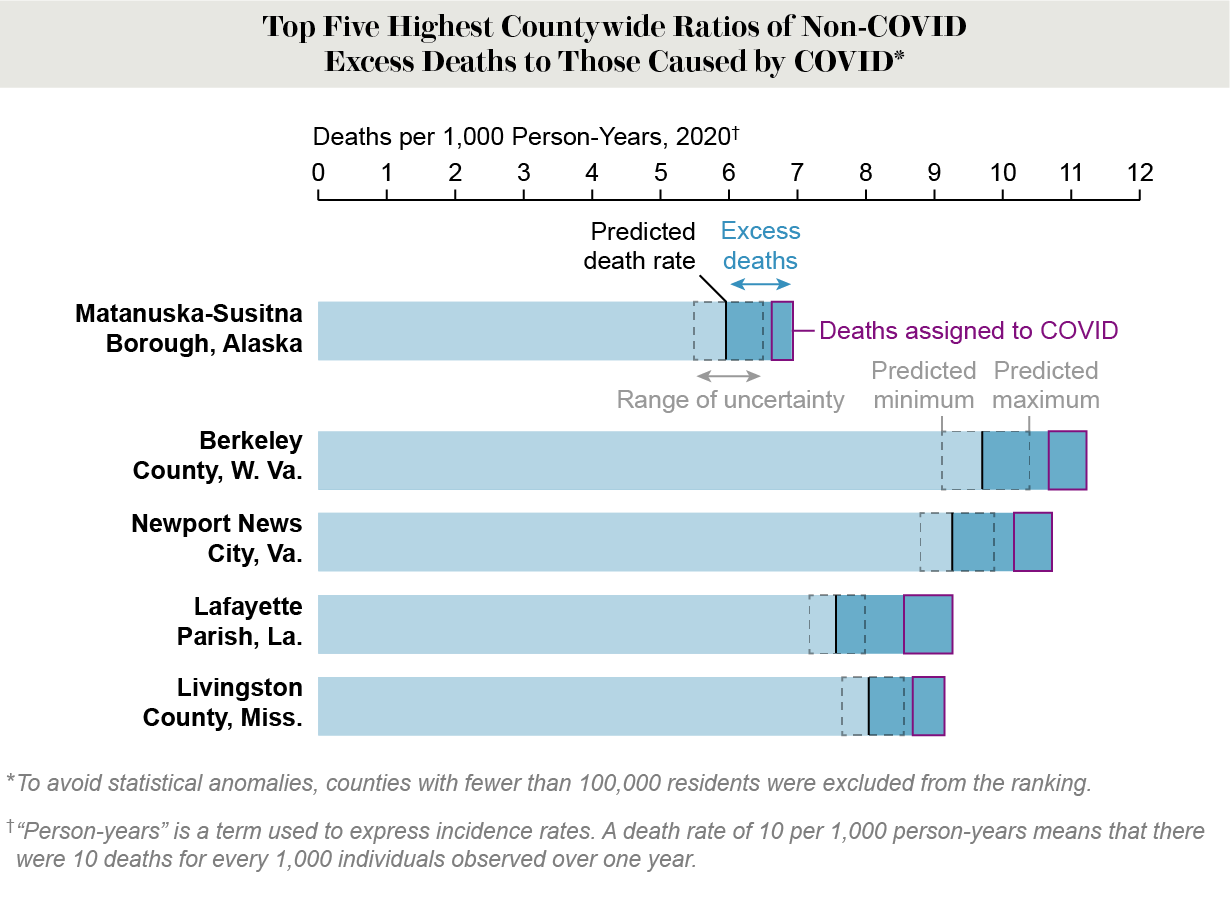

The chart below reveals the counties that had the highest ratios of non-COVID excess deaths to those assigned to COVID.

The county-level data also revealed trends that were not apparent from state-level figures. Take Florida: the state’s official numbers are often held up as being no worse than average in terms of COVID deaths, despite its governor taking a relatively relaxed approach to pandemic-related restrictions on activities. But Stokes’s team observed a lot more excess deaths not attributed to COVID in some of Florida’s rural counties, compared with more urban ones.

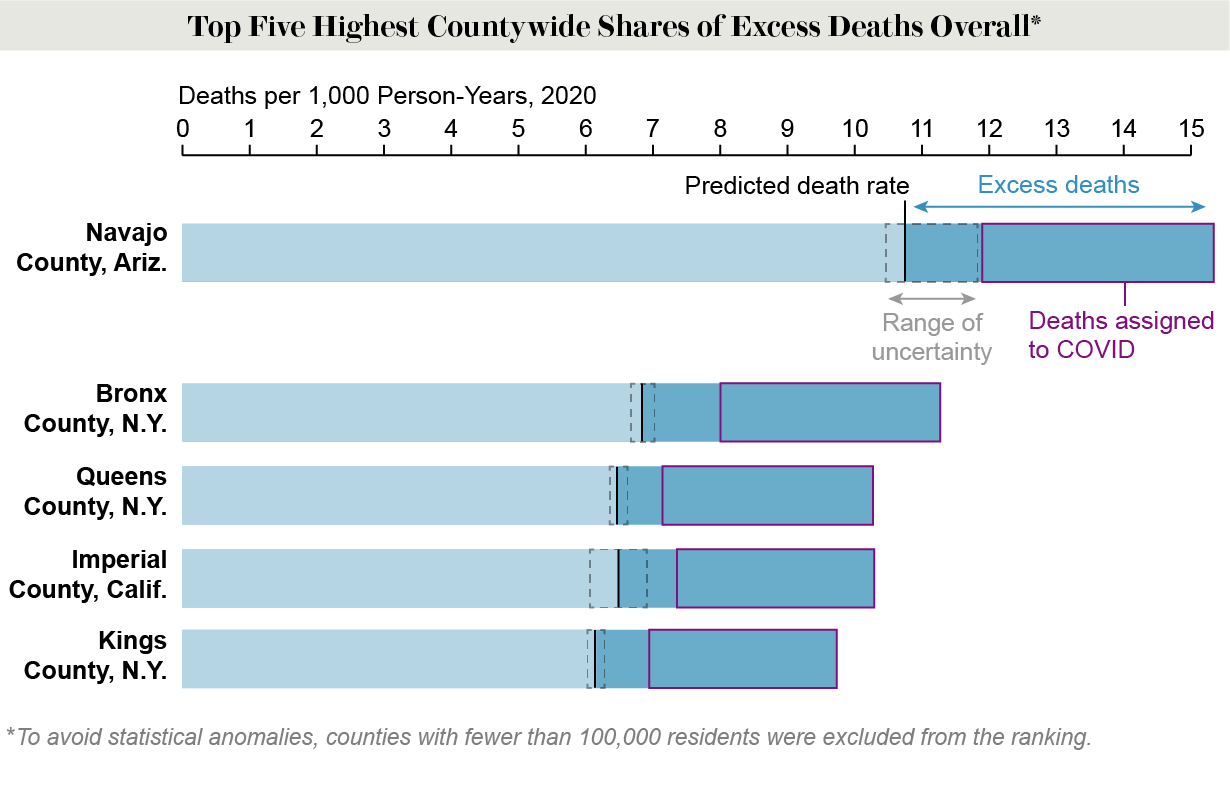

Yet rural counties were not the only places that saw high numbers of excess deaths. Three of the five American counties with the most excess deaths overall were in New York City, which was the epicenter of the pandemic last spring.

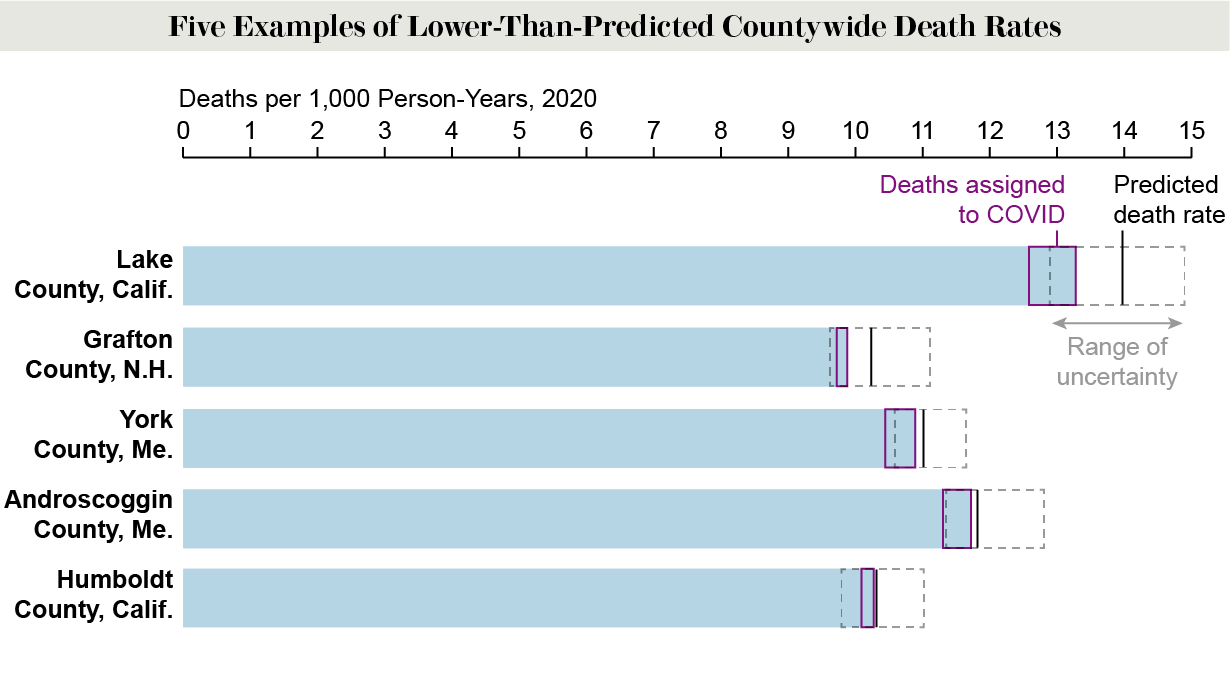

Interestingly, in some counties in New England’s metropolitan areas, reported COVID deaths actually exceeded excess deaths in 2020, suggesting these regions had reductions in other causes of death. For example, far fewer people may have died from the flu (which virtually disappeared during the pandemic)—as a result of many taking public health precautions and working from home.

There are a number of possible reasons for county-level gaps between excess deaths and reported COVID deaths. One is the lack of available testing early in the pandemic, when many health care systems were overwhelmed. And COVID was less likely to be listed on death certificates without a positive test. Many people who died of the illness were in a nursing home, where they could not always get a test. Others died at home because they could not get to a hospital in time or were afraid to go to one. Many deaths attributed to causes such as Alzheimer’s disease or a heart attack may have actually resulted from COVID.

Another possibility is that differences in how deaths are certified—and possibly political bias—played a role in the variation seen among counties. Unlike urban areas, where doctors or medical examiners often certify deaths, in many rural counties, this job is done by coroners, coroner-sheriffs or other elected or appointed officials who do not have a medical background. “In Texas, for example, while most metro counties have their own medical examiner for death investigation, rural areas frequently rely on justices of the peace,” Stokes says. These justices “often lack medical training and resources for postmortem testing and may have their own political biases that affect death certification.” Rural U.S. areas also tend to support conservative politicians, many of whom questioned or denied the severity of the election-year pandemic threat. Stokes and his team hypothesize that the political views of these officials may have influenced their decisions not to list COVID as the primary cause of death.

The gap between COVID deaths and excess deaths could also reflect an increase in other causes of mortality that were indirectly affected by the pandemic. These could include acute illnesses, such as a heart attack or stroke, that were left untreated because hospitals were overwhelmed and people were avoiding care; chronic illnesses, such as cancer or diabetes, that were not controlled because the pandemic’s economic impacts made it harder to access and afford treatment; and an increase in social isolation that may have led to deaths from suicide or a drug overdose.

The study did not try to determine the proportion of a given county’s excess deaths that may have resulted directly from COVID versus related factors such as those described above, because detailed county-level cause-of-death data have not yet been released. The national mortality information in these analyses was provisional and may be subject to change when final data are released. The data set also included independent cities that are not part of a larger county.

The research “provides further additional evidence that the burden of the pandemic is higher than the reported numbers and some places in particular might have a larger number of unaccounted for COVID deaths,” says Daniel Weinberger, an associate professor of epidemiology at the Yale School of Public Health, who co-authored a previous study of excess deaths but was not involved in the new analysis. He notes, however, that “more work is needed to untangle the contribution of how much are direct viral deaths and how much are unrelated changes due to disruptions in health care.”

Kirsten Bibbins-Domingo, chair of the department of epidemiology and biostatistics at the University of California, San Francisco, emphasizes the importance of understanding these trends. “We are sort of numb to the number of people who have died of COVID,” says Bibbins-Domingo, who was not involved in the new study. “This phenomenally detailed county-level analysis tells us that there’s a lot of variation, and that variation falls deeply along racial and class lines. In places that have lower income, in places with more minority populations, in places with worse health status to begin with, we see that the impacts of the pandemic are likely far greater than even the stark disparities in the pandemic have suggested thus far.”

Stokes and his colleagues recently published another study on excess deaths among clusters of counties in PLOS Medicine. This work found that low-income communities, as well as those with a high proportion of Black people, had greater numbers of excess deaths that were not assigned to COVID. Many people of color work in essential jobs that have put them at a greater risk of exposure to the novel coronavirus, and many of them have had poorer health as a result of decades of income inequality and structural racism. “The whole overarching picture of this research really needs to focus on the underlying systems that contributed to vulnerability during the pandemic,” says Dielle Lundberg, a research fellow at Boston University, who was a co-author of both the new preprint and the PLOS Medicine study. “If we want to improve public health, we need to address these underlying systems.”

Stokes worries that an undercounting of COVID deaths may be fueling vaccine hesitancy in many areas. His team has looked at the proportion of excess deaths that were not attributed to COVID and how it relates to vaccine uptake and hesitancy. “There is a clear and compelling pattern whereby places with the most vaccine hesitancy and the lowest vaccine uptake are the same communities that had the most excess deaths not assigned to COVID,” he says. “If we rectify those undercounts, the question is: Could that have immediate impact on vaccine uptake in communities?”

Perhaps the biggest takeaway from this research is that U.S. counties need more systematic ways of certifying deaths, Bibbins-Domingo says. “It’s not very sexy to say that we need to be able to collect better data,” she notes. “But when data drives policy—and data drives policy that is aimed at addressing inequities—good data collection is absolutely critical.”

You are providing good knowledge. It is really helpful and factual to increase one's knowledge. Well you should check this out too Rapid Covid 19 testing in NYC. And again please continue sharing your data it's really helpful. Thank you.

ReplyDelete