Social science offers valuable lessons about ways to convince those who are hesitant about the shots

Operation Warp Speed has certainly lived up to its name. The arrival of the first coronavirus vaccines less than a year after the pandemic began blew away the previous development record of four years, which was held by the mumps vaccine. Now social scientists and public health communications pros must clear another hurdle: ensuring that enough people actually roll up their sleeves and give the shots a shot—two doses per person for the Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna vaccines that won emergency use authorization from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in mid-December. Somewhere between 60 and 90 percent of adults and children must be vaccinated or have antibodies resulting from infection in order to arrive at the safe harbor known as herd immunity, where the whole community is protected.

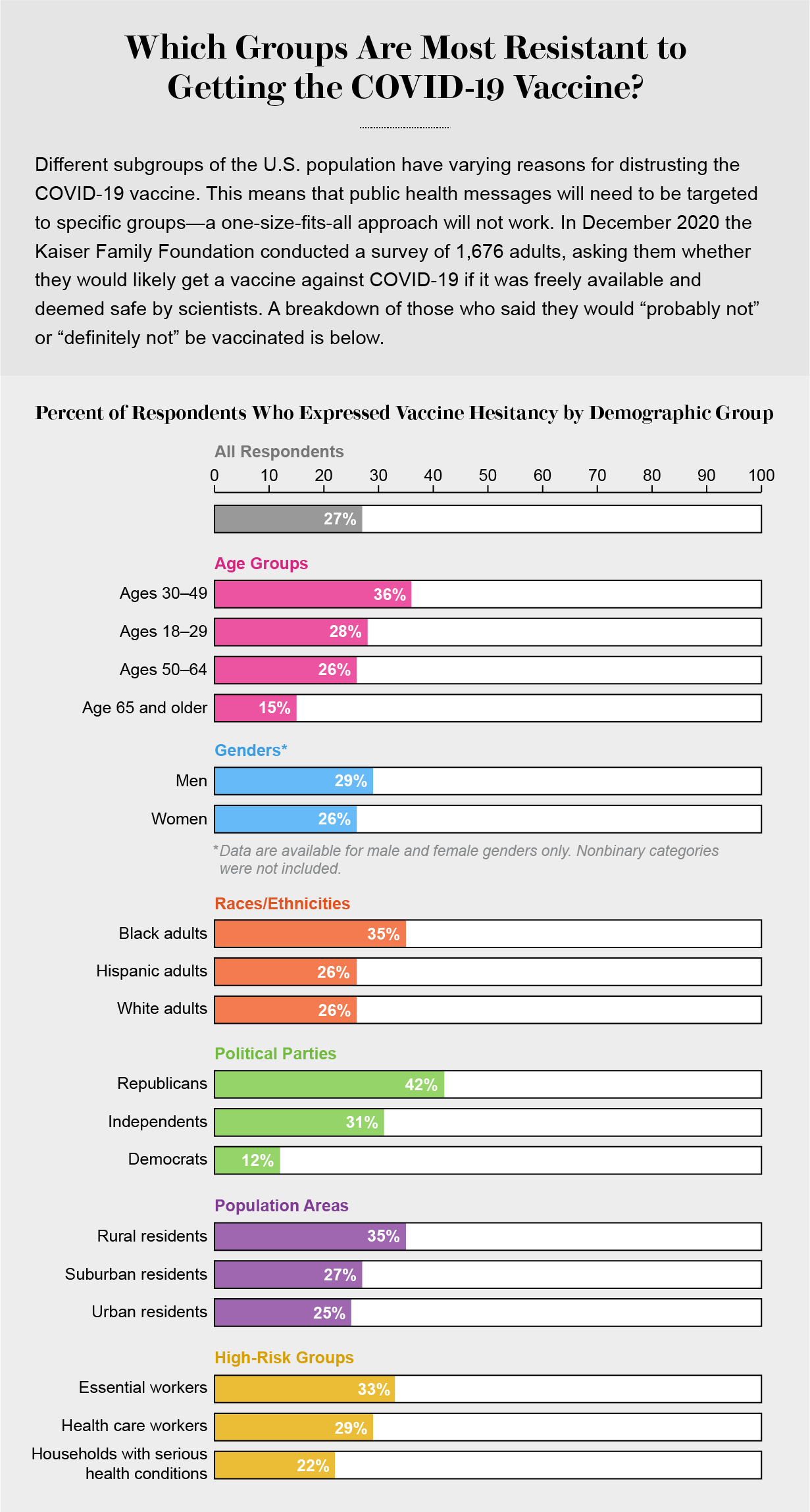

After months of rising death tolls, a collapsing economy, activity restrictions and fears of falling ill, many Americans are eager to be immunized. In a nationally representative survey of 1,676 U.S. adults conducted in early December by the Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF), 71 percent said they would definitely or probably get a vaccine for COVID-19, up from 63 percent in September. A November Pew Research Center survey showed a similar rise.

But there are large segments of the U.S. population that remain reluctant or opposed to receiving the vaccines. In the KFF poll, 42 percent of Republicans said they definitely or probably would not. The same was true for 35 percent of Black adults, who, as a group, have borne a disproportionate share of sickness and death from COVID-19. Also deeply hesitant were 35 percent of rural residents, 36 percent of adults ages 30 to 49, and—especially worrisome given their public-facing roles—33 percent of essential workers and 29 percent of those who work in a health care delivery setting.

For the reluctant and distrustful, it will take targeted actions and communication strategies that speak to the specific concerns of each group to move them toward accepting the new vaccines. “The most effective messenger in the Black community won’t be the same one as among Republicans, obviously,” says political scientist Brendan Nyhan of Dartmouth College, who studies misperceptions about health care and politics. “We need to meet each community where they are and understand the reasons for their mistrust.”

Even among the willing, it will take a concerted effort by public health officials to ensure that good intentions translate into action. Whether it is getting out to vote or showing up for a vaccination, one third to two thirds of people who say they will do something wind up flaking out, says Katy Milkman, co-director of the Behavior Change for Good Initiative at the University of Pennsylvania, where she researches ways to close this “intention-action gap.”

Health communications specialists like to say that “public health moves at the speed of trust.” Fortunately, research by Nyhan, Milkman and many others points to ways to build that trust and prompt more people to step up and get vaccinated. Surprisingly, these strategies include not directly contradicting people’s mistaken ideas about vaccine dangers and instead approaching them with empathy. That approach means acknowledging historical reasons for medical distrust among people of color and working with leaders within their communities. For Republican skeptics, it may involve messages that are less about the risks of COVID and more about giving the economy a shot in the arm.

The Willing Majority

Most Americans want to be vaccinated against SARS-CoV-2, the virus responsible for the deaths of one in 1,000 Americans. Seniors are especially eager, according to the KFF survey: 85 percent of adults ages 65 and older said they probably or definitely will get a vaccine. Their enthusiasm makes sense, given their heightened vulnerability to a life-threatening case of COVID-19. Elderly people in nursing homes and assisted-living facilities are among the first to receive the vaccines, which, under federal plans, are being delivered directly to such residences by the country’s two largest pharmacy chains, CVS Health and Walgreens, along with some pharmacies in the Managed Health Care Associates network.

Seniors living independently and younger people will have to wait their turn for wider distribution—and then make a personal effort to get their shots. That is where things often break down, Milkman says. When people fail to get their annual flu shot, for example, she says, “there is an assumption of some deep-seated desire not to do it, some deep fear of undesirable side effects. But actually, a really common reason is that they forget. It’s a little bit of hassle, and they don’t get around to it.”

Research shows that some surprisingly simple interventions can make a difference. The one with the biggest proved impact, Milkman says, is to make the desired action—in this case, vaccination—the default. A 2010 study at Rutgers University showed that informing people that a dose of flu vaccine was waiting for them at a specified time and place (although the appointment could be changed) boosted their vaccination rate by 36 percent, compared with a control group that was e-mailed a Web link to schedule their own appointment. In other words, opt out works better than opt in.

Another effective tactic is sending relentless reminders. Milkman points to a 2019 study involving 1,104 patients with tuberculosis in Kenya. Its goal was to get more people to complete their drug treatment regimen. About half of the participants were assigned to a control group. The others got daily text messages reminding them to take their meds. If they did not respond in the affirmative, they got two more text reminders that day and, if that failed, phone calls. The strategy was, “basically, just nagging the heck out of them,” as Milkman puts it. Nearly 96 percent of patients in the nagged group were treated successfully, compared with about 87 percent of the control group.

To determine what kinds of reminders work best, Milkman and her colleagues Angela Duckworth and Mitesh Patel have conducted studies with Walmart pharmacies and with two regional health care systems to field-test a variety of text messages designed to nudge people toward getting the influenza vaccine. The team is still scrutinizing its data, but early analyses of vaccination records from the health care systems suggest that simple reminders to request a flu shot, sent days or hours before a doctor’s appointment, appear to be “really valuable,” Milkman says. “We tried to be interactive and funny, and I’m not sure that any of that was necessary,” she notes. The study, whose results will be released early this year, was timed to inform efforts around the coronavirus vaccines.

The Movable Middle

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services is rolling out its own messaging and communication plan for the vaccines, some of which feature such high-credibility figures as Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and Surgeon General Jerome Adams. According to a preliminary document obtained by the New York Times, the campaign will target “the Movable Middle”—people who may have some hesitations about getting the shot but who are not dead set against it.

Despite all the publicity the anti-vaccination movement has received in recent years, social scientists who study vaccine refusal say hardcore anti-vaxxers are a tiny group and are probably not worth worrying about. (For instance, only 2.5 percent of U.S. kindergartners were exempted from all vaccines, according to 2019 CDC data.) “We are more interested in targeting people who might be ambivalent to nudge them in the right direction,” says Rupali Limaye, a health communication scientist at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

Research by Limaye and others reveals some dos and don’ts about nudging the somewhat wary. “One thing that we’ve learned very clearly is not to correct misperceptions because people feel as though we are being dismissive,” she says. In fact, a large 2014 study led by Nyhan found that informing parents that there were no credible data linking autism with the vaccine for measles, mumps, and rubella and providing facts about the very real dangers of these diseases had no impact on their intention to vaccinate a child. Instead such a strategy actually hardened negative views among the most vaccine-averse.

Rather than contradicting someone’s views, Limaye says, it is better to “come at this with empathy.” She suggests responding to misinformation “by saying something like, ‘There’s a lot of information out there, and some of it is true, and some of it is not true. Let me tell you what I know.’” That kind of reply, Limaye says, “helps [people] feel that they are being listened to.”

Medical personnel can also build rapport by framing the decision in a personal way: “Let me tell you why I vaccinated my own children.” Such statements leverage the single most trusted source of health information for most Americans: their own health care providers. The fact that health care workers are first in line for the coronavirus vaccines gives them a crucial opportunity to set an example and offer first-person validation for worried individuals.

The gradual and very public rollout of the new vaccines provides the opportunity to make vaccination for COVID a new norm—something that everyone will be doing. Studies show people make choices such as buying flood insurance or solar panels for their home because their neighbors have done so, “and the exact same thing is true for vaccinations,” observes Dietram Scheufele, a professor of life sciences communication at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. He and Milkman think it might be a good idea to hand out stickers that say, “I got vaccinated,” much like the “I voted” stickers used to propel people to the polls, or to do the digital equivalent with a Facebook profile filter. If celebrities and sports stars join the trend, so much the better.

Reluctant Minority Groups

More specific and targeted messages and actions will be needed to address vaccine hesitancy among minority racial and ethnic groups. The obstacles for these populations tend to fall into two buckets: those related to access and those related to trust, says Samantha Artiga, vice president and director of the Kaiser Family Foundation’s Racial Equity and Health Policy Program. Access barriers include where and when the vaccine is available: Can individuals who do not own a car or who work late-night shifts easily get immunized? What about workers who have no unpaid sick leave and have legitimate fears about side effects from the shots? Vaccine distribution and communication plans will need to address these issues and avoid mistakes made with the availability of COVID testing.

Another reason access can be a problem for people of color is that they are less likely to have health insurance and an existing relationship with a provider. “Ensuring that people understand that there is no cost associated with the vaccine will be very important,” Artiga says.

Issues involving trust are rooted in past and present discrimination. Historical abuses by the U.S. government such as the forced sterilization of thousands of Native American women and the unethical Tuskegee study conducted on Black men with syphilis—both of which continued into the 1970s—have left lingering fears and skepticism of government research and health authorities, experts point out. People of color continue to face racism in the health care system, including barriers to treatment and testing for COVID, which has killed nearly three times as many Black, Hispanic and Native Americans as white ones. This inequity was highlighted in the tragic case of Susan Moore, a Black doctor in Indiana who publicly decried bias in her medical treatment for COVID. Moore succumbed to the infection in late December.

“You can’t say, ‘It’s time for the vaccine now; believe in us,’ leaving aside the entire atmosphere of negligence, haphazardness and inequity surrounding caring for people with COVID and preventing COVID,” says Zackary Berger, a bioethicist and associate professor of medicine at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine. Berger is critical, for example, of the way New York City handled communication about the pandemic with Orthodox Jewish communities, some of which have shown resistance to physical distancing measures and have a history of vaccine hesitancy. Shuttering schools in the zip codes where such individuals live and calling them out publicly for congregating in large numbers has made them feel targeted rather than protected. To earn their trust in the new vaccines, public health leaders will need to seek out “sources of authority” within those communities, Berger says. “You have to listen and work with them,” he adds.

Immigrants, particularly those who are undocumented, may have other concerns about getting vaccinated, such as having their data shared with immigration authorities. In the past few years, such fears led many immigrants to become reluctant to rely on government services, Artiga points out. They might not show up for vaccination, she says, unless state and local health authorities are “really clear about what information is being collected as people obtain the vaccine, what that information will be used for, what it can’t be used for and where it is going.”

For Black Americans, health authorities will need to address heightened concerns about vaccine side effects. In the KFF survey, 71 percent of vaccine-hesitant Black respondents reported this was their number-one issue with COVID immunizations, whereas 59 percent of all people disinclined to get the shot did so. Black respondents were also twice as likely to worry they might get COVID-19 from immunization. Given high levels of medical mistrust, “we must be forthcoming about what we know and what we don’t know about the new vaccine,” says Letitia Dzirasa, health commissioner of Baltimore.

Involving a variety of trusted messengers with roots in communities of color was one takeaway from a Baltimore flu vaccine campaign conducted last year. Dzirasa’s team worked with local faith leaders and historically Black colleges and held focus groups “to understand what messaging would most speak to them,” she says. To reach younger African Americans, she and her colleagues held a Webinar with a local pastor who has a strong Black millennial following on social media, “then we chopped up [the video] and put it on Instagram,” Dzirasa says. Such community contacts and social media influencers will be a vital part of the city’s COVID vaccination effort.

Skeptical Republicans

An unusual aspect of COVID vaccine hesitancy in the U.S. is its political dimension, which is not a consideration with other adult vaccines, such as those for influenza or shingles. Throughout the pandemic, President Donald Trump, other Republican leaders and right-wing media have downplayed the risks of the disease, discounted the value of face masks and other protective measures, and questioned official infection and fatality numbers—all of which has muddied attitudes toward the vaccines.

More than four out of 10 Republicans told KFF pollsters that they do not want to be immunized. And unlike every other group polled, they trusted one figure more than their own doctors for COVID-related information: Trump. Asked to name their most trusted sources, 85 percent of vaccine-hesitant Republicans named the president. Their own doctor/provider ranked a distant second, at 67 percent. And the FDA and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention were trusted by only one third.

Health communication experts note that this situation is unprecedented and, as with other reluctant groups, calls for a specific response. It should help, they say, that such prominent Republicans as Vice President Mike Pence and Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell got vaccinated on camera. “It would be great if all the Fox News anchors got vaccinated on-air,” Nyhan says. Most powerful of all, however, would be Trump doing the same—an example he has not publicly committed to setting.

Scheufele suggests that more Republicans might be persuaded if health authorities framed vaccine messages in ways “that resonate with their core values.” Such messages might emphasize that the sooner the American public is vaccinated, the sooner we can fully open restaurants, hotels, gyms, and churches and return to an economy that allows businesses to thrive. That kind of message will have broad crossover appeal regardless of political persuasion, Limaye points out. “All of us want to get back to normal.”

Moving Targets

With so many unknowns about the two current vaccines and those awaiting FDA authorization—including rarer side effects and how long protection will last—communication will need to be nimble and responsive. Transparency will be key as new phases roll out, problems arise and data emerge, according to experts who presented at a recent National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine Webinar on vaccine confidence. The harder part, they noted, will be dealing with misinformation and irresponsible reporting, such as news stories that highlight vaccine mishaps and adverse effects without providing context on how often they occur. That has already been a problem with some reports about an Alaskan health care worker who suffered a severe allergic reaction without noting that tens of thousands had been vaccinated without major incident.

No matter how nimble, well-targeted and research-based vaccine communication turns out to be, it will not paper over the underlying reasons for distrust or the structural disparities in public health that the pandemic has revealed. “Striving to be a good communicator and empathetic is of ethical importance. It makes health care better, but it’s not a systemic solution,” says medical ethicist Berger. He and other experts hope that if the vaccines usher in a postpandemic return to “normal,” it will be a new normal with far fewer inequities.

Comments

Post a Comment